by Robert Moore, Ph.D., CTS, BCETS

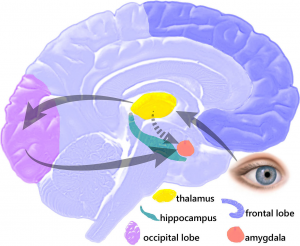

On the other hand, sometimes there is, or we think there may be, a serious threat to our wellbeing or that of a loved one. Knowingly or unknowingly, we may be reminded of a previous threatening situation, loss or injury. Then, our inner alarm goes off; our wise and thoughtful hippocampus and other analytic brain parts get overruled, and the amygdala takes over.

The amygdala, part of our limbic system, heads our emergency response team. When we’re confronted with danger, it cuts in and abruptly “hijacks” (neurochemically quiets) our more mindful hippocampus[1]. Its purpose is to create an emotional state of alarm, and trigger the fight or flight response needed for our survival. The amygdala in control renders us entirely unfit for anything but an immediate and urgent struggle to return to safety and comfort.

The problem is that, long after a threatening or traumatic incident has passed, the amygdala can remain painfully sensitive and reactive, not only to our occasional memory of that prior trauma, but to anything that even remotely resembles it, whether truly dangerous or not.

This is the mechanism of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It’s “normal,” because it represents the standard, although rather primitive way the amygdala alerts us to potential threats by noting the similarity of some element of our current environment to one or more “traumatically encoded” past experiences.

Endlessly vigilant, the amygdala can signal danger in response to our most fleeting perception or fractional memory of a prior trauma by giving us an emotional jolt. No problem when danger actually is imminent. More often than not, though, the resemblance of our present circumstance to a past misfortune turns out to be superficial, and our warning jolt is a false alarm, sometimes quite a debilitating one.

Until recently, health professionals have regarded the amygdala’s frequent false alarms (e.g., hypervigilance) as a manageable but irreversible consequence of trauma (“once traumatically encoded, always traumatically encoded”). In many areas of service to trauma survivors, that historically understandable but mistaken view prevails to this day. It’s supported, as well, by the equally understandable belief on the street that we get stuck for life with the emotional consequences of our most hurtful experiences and must, thereafter, simply learn to cope. This is an inference incorrectly drawn from the fact that once a hurtful experience has come and gone, it cannot be undone.

Accordingly, the psychological services have mainly helped trauma survivors to minimize or manage their intrusive post-traumatic episodes, but with the expectation that, although their upsetting memories may fade somewhat over time, they are likely to recur in some form indefinitely. Unfortunately this expectation all but closes the door on any hope of complete and permanent relief from post-traumatic stress, a shortfall seen in the vulnerability to triggering of many trauma survivors in recovery, decades after their abuses.

Fortunately, endless post-traumatic symptom management and coping are nearing the end of their days. We now have clear and reliable evidence of the total reversibility of specific incident, complex and developmental (childhood) trauma and at least one well-established technique that delivers on the promise.

Traumatic Incident Reduction (TIR), available in many locations around the world, effectively eradicates the post-traumatic effects of a wide range of both individual and multiple (long-term, complex or sequential) traumatic incidents and challenging times of life. Examples include: domestic and combat injuries, physical and emotional abuse, rape and other crimes of violence, industrial accidents, overwhelming loss, postpartum and postoperative stress. TIR also works well with those non-trauma-specific but broadly pervasive adult effects of adverse childhood experience and most otherwise unaccountable (absent flashback) bouts of anger, anxiety and depression.

The TIR protocol is somewhat atypical. Instead of challenging, suppressing or attempting to short-circuit the amygdala’s alarm, it takes advantage of the organ’s often overlooked, native ability to un-encode, or actually reverse and reclassify even a long-standing traumatically encoded experience.

Once un-encoded (a remarkably straightforward procedure for a TIR-trained facilitator), the memory of the experience, as well as its previously toxic secondary associations, permanently lose all connection to the amygdala’s trauma signaling system and any further ability to be triggered post-traumatically. What immediately follows is not only the full resolution of the client’s PTSD, or other trauma-related symptoms, but a spontaneous and welcome surge in his or her post-traumatic growth and wellbeing.

This is not to say that conventional procedures have no merit. Many of them in time reduce the frequency or severity of post-traumatic episodes and/or provide useful coping strategies. It’s just that the amygdala won’t give up control of a traumatically encoded experience and put a permanent end to PTSD in response to what most conventional procedures require: discussion between practitioner and client, either of the experience itself, or of how to deal with its post-traumatic effects. The two approaches are mutually exclusive.

Therapist-client discussions — in fact, caring conversations of all sorts — are substantially hippocampal in nature. That is, they’re generally intelligent, analytic, understanding, compassionate, reassuring, practical, didactic, advice-giving, and so forth. As such, they require and create a client brain-state quite opposite from the one needed for the amygdala to reverse itself with finality and reclassify a prior trauma as no longer active, relevant or eligible for any subsequent emergency response.

Such a reversal needs a brain-state that occurs only when the amygdala is brought into the client’s “working memory” and allowed to control as much of the brain’s “executive function” as the traumatic encoding of the target incident requires. This is not as complex or dicey as it may sound. It’s exactly what the amygdala is designed to do and very good at doing in threatening circumstances: take over. Accordingly, the TIR protocol facilitates this shift of control from hippocampus to amygdala by carefully guiding the client’s attention in keeping with several rather strict principles (bear in mind that anything resembling conventional therapist-client dialogue puts the client’s hippocampus and prefrontal cortex back in control, scuttling the procedure).

The amygdala, a small but incredibly stubborn organ, refuses to listen to reason. So, we need to cater to it almost exclusively from early on in the process.

Determined effort (client counter-intention) can somewhat weaken its effects but, again, that would be opposing it hippocampally. By design, the amygdala cannot be talked out of its responsibility to sound an alarm (thus triggering a post-traumatic reaction) by sheer logic, intelligence or authority when, rightly or wrongly, it thinks our pants are on fire.

Pardon the anthropomorphisms and other analogies here… but for the amygdala to “realize” or “learn” post-traumatically that its alarms with respect to a particular past disaster are outdated and no longer relevant (which it must for traumatic un-encoding to occur), it must have the freedom to play out its original, protective repertoire for the careful inspection of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. And it must do this unopposed and without reframing, whether by therapists, caring friends or family, in the other-voiceless “sound-proof room” of the client’s working memory.

We want the two competing neurological parties to their host’s emotional welfare to reach complete accord regarding every relevant aspect of the incident in question. This needs a carefully structured review of the amygdala’s original reasons for declaring (and post-traumatically re-declaring) the emergency and suppressing the normal operation of the prefrontal cortex, followed by the hippocampal/cerebral group’s reply-argument for a revised, more up-to-date understanding of the experience. An uncommenting facilitator assists this. With the current reality stably on the cerebral side of the argument, the amygdala invariably catches on and, before long, sees and agrees that the dire situation, to which it had thought all subsequent reminders justified an alarm, no longer exists.

At that very moment, as the amygdala permanently removes the incident from its trauma “watch list,” the new reality triggers an unmistakably celebratory neurologic reflex in the client. This very often both surprises the client and defies the imagination of a facilitator who had not yet personally witnessed it. Traumatic un-encoding complete, the amygdala then simply leaves the building, never again to trouble itself or its now delighted, often broadly grinning host about the finally resolved incident.

Robert Moore, Ph.D., CTS, BCETS currently resides in Clearwater, Florida. He can be reached by email to moorebob@juno.com

[1] Freedman, J. (2010). Hijacking of the amygdala. Retrieved from http://www.inspirations-unlimited.net/images/Hijack.pdf

This article originally appeared in AMI/TIRA Newsletter, Vol XI, No. 2 (July 2015)